China’s rapid development in mobility and digitalization

China is increasingly recognized as an innovation leader in mobility and digitalization. Companies in mobility services, like Didi or Meituan, in NEV vehicles, such as BYD or Foton, or in technology, like Huawei or Baidu, have sparked global interest in how China is creating an ecosystem to build the future in digitalization and in mobility.

In order to better understand how Chinese and Germans can cooperate and learn from each other in mobility and digitalization, the German state of Hesse has sent a high-level delegation of businesspersons, scientists and policy makers led by Mathias Samson, State Secretary to the German Ministry of Economics, Energy, Transport and Regional Development, State of Hesse, to Beijing and Shenzhen from Sep 2 to Sep 7, 2018. The sustainable mobility team of GIZ China has supported and accompanied this trip.

The delegation met with representatives from government (e.g. Ministry of Transport, or the Economy, Trade and Information Commission of Shenzhen Municipality), established companies (e.g. Foton, BYD, Huawei), unicorn start-ups (e.g. Royole, BOE) and start-up accelerators (e.g. HAX Accelerator in Shenzhen or Innoway in Beijing). After seeing the rapid development of the infrastructure, the companies and the ubiquity of new technology, one key conclusion trumped the take-aways for the participants:

The future of mobility and technology is hardly predictable.

This message was not only experienced directly, for example, when participants were not able to pay with “old-fashioned” credit cards, as sellers required WeChat Pay (i.e. payment with the WeChat App), or when they failed to hail a cab on the streets, as cabs are hailed digitally. Sven Patuschka, the Executive Vice President R&D Technology Asia of Volkswagen, used a “historical” comparison when noting that in 2007, few people would have predicted the impact of the first iphone on our lives in 2018. Similarly, Isbrand Ho, Managing Director of BYD Europe remembered that in 2007 he was sure that Motorola would still be a dominant phone maker in 2018. In fact, however, the then little-known Chinese brand Huawei has become today’s global number 2 phone maker and number one telecommunications equipment manufacturer, while Motorola has lost its leading market position.

China over the last two decades has been successful in providing a thriving eco-system to build global tech giants. BYD was only founded in 1995. Today, BYD employs about 220.000 people, 450 of which in Europe, where it produces buses in Hungary and has a research center in Amsterdam. The speed of change within BYD is also impressive: the company started as a producer of smartphone batteries in 1995, started building BYD cars in 2005, produced its first electric buses in 2009. Today, BYD has not only supplied 95% of Shenzhen’s 17,000 electric buses, but many more of the total of 250.000 electric buses sold until 2017 in China and is now expanding its portfolio to include Monorail systems.

New Energy Vehicles (NEVs) in China

According to BYD’s Mr. Isbrand Ho, one reason for the future success of BYD and for the spread of NEVs is that governments promote the use of NEVs (both private and public), by banning Diesel vehicles and subsidizing NEV purchases. The city of Shenzhen, for example, has required that Shenzhen’s taxi fleet is fully electric by the end of 2018. To finance the subsidies given to taxi owners, taxi passengers in Shenzhen are required to pay a small fee when using a taxi. But, as Mr. Ho pointed out, NEVs are not only good for reducing local emissions, but also for balancing the electric grid when feeding energy from renewable sources, e.g. from wind or solar, into the grid: batteries of NEVs can provide a buffer for excess energy that is generated when there is lots of sun or wind and can feed it back into the grid when energy production is lower.

Particularly new energy buses sparked the interest of the participants, as German cities like Wiesbaden (the capital of the state of Hessen) aim to replace diesel buses with electric buses. The delegates visited a charging station of electric buses in the north of Beijing to learn more about the operation of electric buses. Within Beijing’s 3rd ring, buses serve about 350 million passengers per year with 102 bus lines. Of the 3,600 buses in operation, 700 are electric buses. They can be charged to 80% capacity within 25 minutes to have an operating distance of about 100 km.

NEVs and electric mobility also play an ever-increasing role for Volkswagen, as the delegation experienced in Volkswagen’s Future Mobility Center in Beijing. As a service for their customers, Volkswagen’s Eric Hou showed the participants the Car-Net App developed by Volkswagen, which shows the availability and functioning of about 50% of the publicly available NEV-charging stations in China. Giving information on these charging poles requires constant updating, as charging stations are constantly added to the grid in China: Just from January 2017 to March 2018 the available AC charging poles in China increased from 29,905 to 57,338, while the DC charging poles increased from 16,879 to 22,827 poles.

Autonomous mobility and big data

Besides electric mobility, Volkswagen (similar to its Chinese and German competitors) puts many resources in developing autonomous vehicles. Alex Pesch from Audi (a brand of the Volkswagen Group) introduced the new Audi A8 to the delegation, which is able to drive autonomously on highways and other situations (what is called “Level III autonomous driving”, see here for more information on autonomous mobility). Alex Pesch is convinced that autonomous driving is technically possible in the near future for Chinese and German cars. That is despite the differences in approaches to autonomous driving in China (which prefers a solution that controls autonomous cars centrally or “in the cloud” through interconnected vehicles – ICVs) and Germany (which prefers a solution where cars have the intelligence on board). The main hurdle for the widespread introduction of autonomous driving, according to Volkswagen and Mr. Ho from BYD, are the legal uncertainties, both in terms of liability and also in terms of standards. The obvious example is the question of liability when an autonomous car hits a pedestrian, but also the liability question of two autonomous cars crashing is yet unresolved. Thus, autonomous functions will probably first start to be employed in more narrow circumstances, such as to accelerate more swiftly at traffic lights in order to get more cars through a green light.

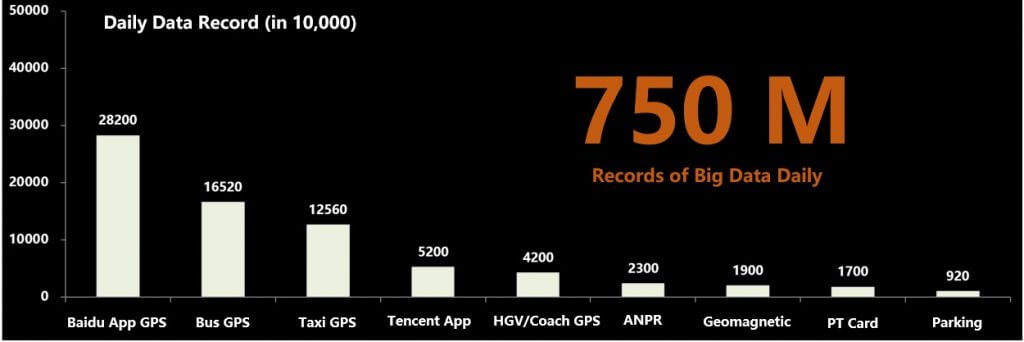

Particularly in the context of introducing interconnected vehicles, the widespread introduction of fast mobile internet through 5G telecommunication technology and the efficient use of big data is paramount. During the visit, the delegation got insights into the status of 5G development (Huawei) and into the collection and analysis of big data in transportation planning (Shenzhen Urban Transportation Planning Commission (SUTPC)). Some differences between Germany and China became particularly clear during these two site visits: Huawei employs face-recognizing cameras and software to guarantee safety and to provide live risk analyses, while SUTPC analyzes 750 million records of data from user phones GPS, road-side cameras, Mobikes, taxis, lorries etc. every day (for a more detailed description on big data analysis of SUTPC, see here).

While big data integration and analysis is standard practice for Chinese companies and governments, German data protection laws protect privacy of people over the aggregation of big data in a different way. Thus, participants discussed whether German cities would be able to provide traffic planning and traffic demand management (TDM) similar to SUTPC, which uses all these data to simulate the effects of weather, holidays, construction etc. in order to adapt, for example, traffic lights, traffic routing and bus schedules, on a live and on a predictive basis.

Start-ups and government

As innovation not only comes from incumbents, but also from start-ups, the participants were given access to the Beijing start-up hub Zhongguancun and the Shenzhen start-up accelerator HAX. HAX is located on the top two floors of the world`s largest electronics component market Huangqiangbei in Shenzhen.

Stemming from Shenzhen`s designation as China’s first special economic zone in May 1980 and the subsequent industrial location of many electronics manufacturers (such as Huawei, which was founded in 1987), Huangqianbei electronics market offers everything from resistors to batteries, from LEDs to plugs and cables. The abundance of electronics components as well as the related knowledge allows the startups in HAX to build and test prototypes on a daily basis. HAX business development director Jo-An Ho explained that finishing the development of new products in HAX takes weeks where startups in other locations take months.

During the trip, participants also experienced the role the Chinese national and provincial governments play to support the digital mobility eco-system. Chinese government representatives explained to the delegation that they not only see a strong role in providing government investment funds, stipulating regulation, prohibitive market barriers and subsidies, but also in providing the basic infrastructure for mobility and digitalization, such as 20,000 km of high-speed rail or 1,000 km of subways in both Beijing and Shenzhen until 2025.

Cooperating for a better future

During the whole trip, representatives from both government and private sector in China and Germany repeatedly stressed the need for strong cooperation between Germany and China. This not only includes easy access to each other’s markets, but also a continuously strong exchange on technical and political issues to provide a learning platform for each other. This mutual learning seems particularly relevant in the field of digitalization and mobility, where nothing is as constant as change.