The Chinese Spring Festival marks the beginning of a new year in the lunar calendar. It is known as China’s most celebrated holiday and a time for family reunification. The annual peak in travel associated with the lunar new year is the ultimate stress test for China’s transportation system. During chunyun (春运) translated as Spring Festival Transportation, every year up to 3 billion trips are made within a period of about 40 days1 domestically and to international destinations (compared to 116 million Americans traveling during the Christmas and New Year’s holiday in 20192). With passenger volumes rising annually, chunyun is holding on to its title as the world’s most voluminous human migration. This year’s Chinese Spring Festival Travel Rush, however, coincided with a particular challenge as it came at a time when China faced a major public health crisis with severe societal ramifications: The outbreak of the COVID-19 epidemic, caused by the virus SARS-CoV-2, which is thought to have originated in Wuhan, a hub in China’s transport and logistics network, and had reached pandemic proportions only weeks later.

In the first days of the Spring Festival 20203 before initial transport restrictions were put in place to stall the spread of the epidemic it seemed as if this year’s travel rush would again exceed passenger numbers of previous years. According to the Chinese Ministry of Transport (MoT)4, within the first 10 days (10-19 January) about 758 million trips, an increase of 2.5 per cent compared to 2019, were made with a trip composition as follows:

- 612 million road trips,

- 117 million rail trips (an increase of 20.3 per cent compared to 2019),

- 19.13 million trips by air travel (an increase of 9.1 per cent compared to 2019),

- 8.84 million trips by waterway travel (an increase of 4.8 per cent compared to 2019).

When the Chinese government introduced further measures, hoping to prevent a country-wide spread of the disease, travel volumes dropped significantly. Among those measures were strict travel restrictions, including the limitation or discontinuation of air, rail and partially road passenger and freight traffic in severely affected and at-risk regions, such as the Hubei Province or Beijing. With many people having postponed their journey home from the spring festival vacation or having gotten confined to their travel destination due to government sanctioned lockdowns, trip numbers of return journeys were stretched over an extended period reducing the usual pressure on the transport system during the peak season. Compared to the same period of Spring Festival return journeys in 2019, the number of trips in and out of Beijing dropped by more than 60 per cent from 24-30 January and the total number of trips in the 40-days period reduced almost by half with 1.47 billion passenger trips5. The individual mobility and the transport sector as a whole were significantly affected by the disease control measures taken by the Chinese leadership. The public health crisis had partly put mobility and the world’s largest human migration on hold and more than four months into the epidemic, some restrictions remain in place.

Notwithstanding the collapse of the railway passenger volume during the 2020 Spring Festival Travel Rush, the railway freight volume during the same period showed an increase as compared to previous years. The Beijing Railway Bureau registered a year-on-year increase of 21.8 per cent in cargo traffic. According to China State Railway Group Co., Ltd., China’s railways handled a 0.6 per cent year-on-year increase in freight between January and February 20206 and a plus of 0.2 per cent over the first four months of 2020. These numbers are interpreted as signs of the country’s economic recovery by the Ministry of Transport7 and are fuelling hopes for a continuous increase in the share of carbon-friendly transport modes at least in the freight sector.

Over the course of the crisis, the pivotal role of the transport system has revealed itself to be an ambivalent one: On the one hand, the transport system was instrumental in spreading the pathogen over long distances in a short amount of time, furthering the proliferation of COVID-19 up to the point when severe limitations on travel were enacted. On the other hand, the transport system became critical in supplying hard-hit regions and cities with the desperately needed supplies (e.g. medical supplies, personal protective gear, agricultural produce, etc.) and human resources (e.g. medical professionals). Thus, the active regulation of transportation became an effective means of disease control8.

The current crisis has once more shown the importance of a well-functioning passenger and freight transport systems in increasing the resilience of societies against disasters, be it extreme weather events or epidemics. Thus, the development of resilient, sustainable transport systems plays an even greater role. With this narrative in mind and with the implementation of the 13th Five-Year Plan (FYP) period (2016-2020) coming to an end this year, it is worth having a look at the status quo of China’s transport system and evaluating the opportunities for the upcoming 14th FYP period.

The Evolution of Chinese TransportInfrastructure Development and the “Challenges of Scale”

During the last decades, China underwent a sweeping socio-economic transformation, which accelerated after the opening-up reforms of the late 1970s. The economic opening marks the beginning of the Spring Festival Rush in the 1980s, when rural workers floated into the cities in search of work, leaving the Spring Festival as a rare time to visit families in the rural (and often remote) hometowns9. In recent years, however, reverse traffic flows during the Spring Festival Travel Rush are gaining traction as more and more people prefer to meet up with their relatives in the cities to enjoy the urban qualities lacking in their rural hometowns10 and as people increasingly go on city sightseeing trips during the holidays.

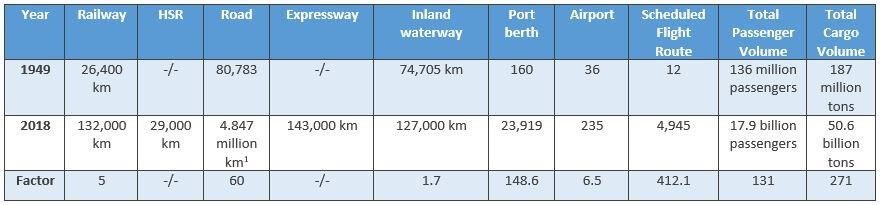

Along with rapid economic growth and urbanisation came the large-scale expansion of the country’s transport infrastructure. By the end of 2018, the road network in China had a total length of 4.847 million kilometers (60 times that of 1949) and the total passenger volume grew from 136 million passengers in 1949 to about 17.9 billion passengers moved by public transport in 2018 (see Table 1).

Furthermore, over the past 10 years the expansion of basic transport infrastructure (mainly road and rail infrastructure) has progressively been shifting from the Eastern provinces, such as Zhejiang or Shandong Province, to the Central and Western provinces, such as Hunan or Sichuan Province. Also, with factories gradually moving production towards the Central provinces and more migrant workers working closer to their hometowns, the focus has shifted from advancing intra-provincial transport networks instead of inter-provincial ones.12

Since the 11th FYP (2006-2010), the promotion of more integrated, efficient transport networks and, in particular, public transport systems has been in the focus of development. Whereas by the end of the 11th FYP period, China only had a high-speed railway (HSR) network of 5,100 km in total length in place, by the end of 2019, it had exceeded its targets of the 13th FYP13 by having built 35,000 km of HSR tracks14, reducing travel times across the country considerably (Beijing-Shanghai 2001 by train: 14h, 2017: 4,5h15). Furthermore, the number of civil airports in the country has risen from 175 in 2010 to a total of 235 in 2018 and the highway network has increased from 4.008 million km in 2010 to 4.847 million km in 2018.

However, with growing transport volumes and the rapid expansion of urban areas and transport infrastructure at an unprecedented scale and pace, challenges arose, such as environmental degradation, severe air pollution, high carbon emissions or the congestion during peak seasons, among others. China’s transport related carbon emissions increased from 397 million tons in 2005 to 1.04 billion tons in 201816, accounting for about 10 per cent of the country’s total emissions. China in its Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) to the Paris Agreement pledged to reach carbon emission peak around the year 2030 and making best efforts to peak earlier. According to the China Academy of Transportation Sciences (CATS), the transport sector is the only sector which most likely will not reach the emission peak by 2030, due to further rising transport volumes in both passenger and freight transport. The corona crisis alone that has contributed to a drop in CO2 emissions by 25 per cent in early March in China is not enough to reverse this trend. Climate activists are already predicting so-called ”revenge pollution” caused by the restart of the economy and the allocation of economic stimulus packages17. Thus, long term policy plans give a more reliable roadmap towards carbon emission reduction than the economic shutdown directives of the pandemic, making it vital that the effects of the pandemic will not be allowed to unhinge the commitment of nations to the Paris Agreement.

Looking Forward: The 14th FYP and the Reinforced Need for Sustainable Transport Development

The Chinese government is currently in preparation of the 14th FYP, directing the country’s socio-economic development from 2021 until 2025. Regarding the transport sector, the direction is clear. The 14th FYP period will lay the foundation for achieving the country’s aim of building an advanced and globally competitive transport system by 2035 and building an internationally highly competitive transport system by 2050 as described in the Outline for Building China’s Strength in Transportpolicy, which, approved by the Communist Party of China Central Committee (CPCCC) and the State Council,was released on 19 September 2019. The outline describes the future vision and roadmap of China’s transport sector with a clear message: China wants to become a global transport superpower by 2050.

While the focus of the 13th FYP was laid on a further expansion of basic transport infrastructure and promoting transport innovations, such as electro-mobility or digitalisation in transport, the 14th FYP will further push the efficient, integrated, green and low carbon development of China’s transport system. This will include increased ambitions in the fields of:

- Further expansion of basic transport infrastructure (high-speed rail but also road infrastructure based on e.g. China National Highway Network Plan 2013-2030),

- Improved inter-city connectivity and coordinated and integrated development of city clusters (such as Jing-Jin-Ji, the Yangtze River Delta or the Pearl River Delta),

- Improvement of rural transport and related integrated urban-rural development,

- Further development and promotion of intermodal transport, green freight and smart logistics solutions,

- Application of big data in transport and related smart traffic management (smart city),

- Promotion and further development of electro-mobility (including battery electric and fuel cell vehicles (BEV and FCV) and related charging and service infrastructure), automated and intelligent and connected vehicles (ICV),

- Integration and promotion of urban public transport and shared mobility,

- Promotion and integrated development of active mobility (including walking, cycling and micro-mobility),

- Promotion and integrated development of barrier-free transport,

- Overall promotion of environmentally friendly, green and low-carbon transport.

The related measures in the fields listed above will be implemented by considering and balancing factors, such as steady economic growth, changing socio-economic conditions, an aging society, the growth potential of transport volumes and emissions, and a society that is increasingly demanding high quality, seamless transport services. The implementation of these goals will also take place against the background of increasing political pressure to make the development of the transport sector more environmentally and climate friendly. In particular, aligning the national targets with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the NDCs is crucial to tackle global climate change effectively and to fulfill the set target of building an advanced and globally competitive transport system by 2035.

Which COVID-19 induced measures, if any, will alter the transport system’s development in the coming years, remains to be seen. However, in the face of the current public health crisis, thinking about the alignment of transport measures with climate protection targets becomes even more relevant in two respects. First, the drop of the modal share of public transport and shared modes worldwide18 since the beginning of the pandemic makes it even more pivotal to promote these modes with high potential for climate-neutrality. Second, the risk of a surge in emissions once the industry fires up its engines again to deliver to a resurgent global demand urges policy maker to counteract and promote green recovery measures not only in the transport sector. The risk of governments across the globe choosing economic resuscitation by all means above climate goals is very real and could roll back much of the incremental progress that had been made prior to the pandemic. Additionally, the crisis has shown that transport planning has to be interdisciplinary and needs to focus on the development of sustainable – inclusive, safe, healthy, equal, affordable, accessible, climate-friendly – transport modes. Not only fields, such as urban planning, demography or energy efficiency, need to be merged with transport planning but also fields, such as epidemic control and, closely linked, disaster risk reduction, in order to be well prepared for the challenges to come in a post-pandemic world.